“Most High”: How—and why—Om builds its minimalist, contemplative metal

Text by Jay Babcock

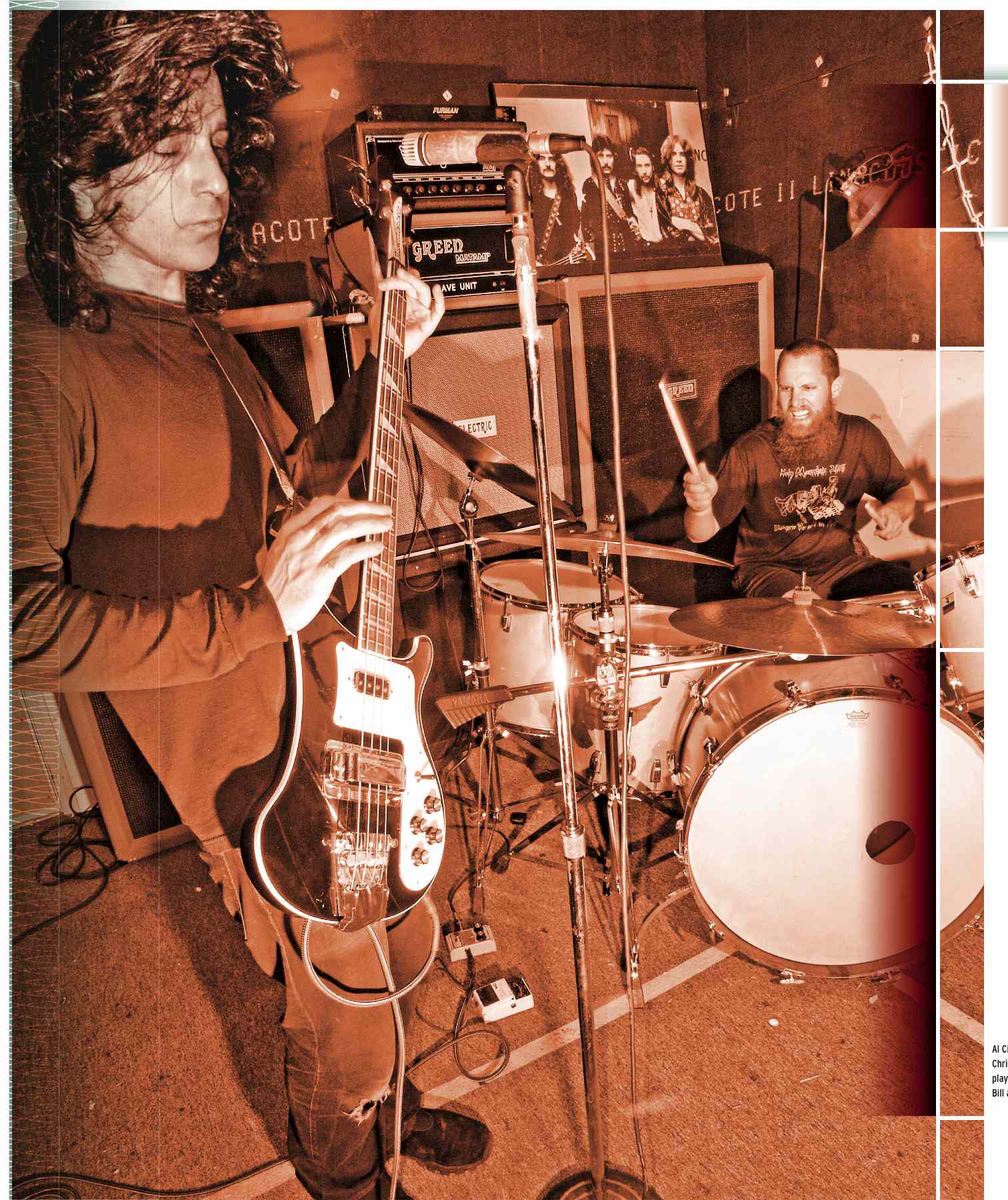

Photos by Lars Knudson

Art direction by W.T. Nelson

Originally published in Arthur No. 22 (May 02006)

Sleep were a tightly focused, intensely dedicated super-heavy riff band from the San Francisco Bay Area who gained a small but devoted following during their time. Even if, like me, you never listened to a note of their music or saw them perform, you probably heard about these guys somewhere: they were the monastic goners who delivered an hour-long narrative song (about caravans of marijuanauts and weedians crossing riff-filled desert lands on an epic drug run) to their record label as their big-label debut (and third overall album)—and then disappeared in the proverbial cloud of smoke… The song/album “Jerusalem” was never released by London/Polygram, the band split up, years passed. Eventually, in 1999, “Jerusalem” was released under still-mysterious circumstances (a better version, entitled “Dopesmoker,” is now available) and the Whispers With Smiles From Those Who Know were proven right: this was a breakthrough masterpiece—deceptively repetitive minimalist heavy metal of such single-minded all-vision that every ridiculous element of the project was rendered sublime by minute three.

When ex-Sleep guitarist Matt Pike’s new band High On Fire debuted in late ’99, it was easy to think this would be the closest you’d ever get to witnessing the now-legendary Sleep: the music heavy yet progressive, the songs endless, the lyrics suitably Old Testament. It was not a repeat of Sleep—there was more emphasis on high velocity—but it was innovative and staggering in its own right.

A closer (which is not to say superior) continuation of “Jerusalem”-era Sleep surfaced in 2004, with the release of Om’s debut album, “Variations on a Theme.” Om was ex-Sleep bassist/vocalist Al Cisneros and ex-Sleep drummer Chris Hakius: a power duo without need of a guitar. “Variations”’ three songs clocked in at 21:16, 11:56 and 11:52. Cisneros’ lyrics—sung (“bravely,” as one friend put it) in an affectless drone-chant—echoed “Jerusalem” but had lost their weed-centricity and become even more hallucinatory; “Approach the grid substrate the sunglows beam to freedom/Winds grieve the codex shine and walks toward the grey” is a typical couplet. A new kind of purity—thinner but deeper, maybe?—had been achieved.

Om’s second album, “Conference of Birds,” is released this month. It has two songs, each over 15 minutes in length. The first, “At Giza,” takes Cisneros and Hakius’ music to an even sparer place of un-distorted bass, drums and vocals. As with these guys’ previous work in Sleep and Om, “Giza” points out new horizons even as the duo hone their own gaze ever sharper.

I spoke with Al Cisneros by telephone from his Bay Area home in late March. Here’s some of our conversation.

Arthur: What were you doing in the seven years between Sleep and Om?

Al Cisneros: For the immediate period following our last Sleep band practice, I honestly creatively and a lot of ways psychologically felt like I had died. It was near catatonic in terms of how depressed and shattered I felt. Chris and I had met in junior high school and then we had met Matt [Pike, Sleep guitarist and High On Fire principal] shortly thereafter. Sleep was a byproduct of that friendship. Of course we loved playing music, but it was kind of a bonus to us and the camaraderie we had during those years, in earlier life. It was a unit.

What actually went down with the band?

It was the typical textbook “bad situation.” When our label actually started to remix the song that we had been working on, “Jerusalem,” around us—despite us… I’ve always compared the way that felt to what it would be like if one had to witness their child suffering and couldn’t leave the room. There is no more depressing, out-of-your-control situation I can think of. I wouldn’t wish that on anybody on this planet. They starved us out after we had held our ripening work intact and endured all of the sacrifices to ensure that it would retain its core. We had really focused everything in our youth and life up to that point where that whole shabuckle took place. I had focused so wholly and entirely on doing Sleep, that’s all I could relate to, so that when I had to walk away from it… I mean, I had to, there was no choice. Worse than what had happened would be to have continued playing without sincerity behind it. I can’t do that. And so, yeah, it was a total blackout: not just on the creative level, just entirely.

But eventually, the music came back…

It took years for that to re-establish itself where naturally lyrics and riffs, concepts and ideas began to come back to my consciousness. After Sleep disbanded, I got a job teaching chess at elementary schools, and used the other time to go to school. It was really an essential time for me to re-calibrate. When music did start to happen though, about four and a half years ago, it was a full flood of stuff. I’d be sitting in class, and I’d be hearing a song. It’s always been an undercurrent in me and it just increased in intensity. So I began to notate all the parts I was hearing, to hum them into a digital tape recorder. For the first year it started to build, and boxes of tapes started to appear. I got to this point where I called up Chris. That afternoon we met up in his backyard. And about a half hour after that, we were making songs in Om.

Is it frightening to have music making itself known to you in that way, as if it had a will of its own?

It’s confirming that you have to play music. You have to do something about it, because you’re not walking up to it and trying to tinker with it; it’s the other way around. I don’t sit and hammer out parts. I get stopped by them. I could be in the middle of a conversation, I could be at work, I could be driving, I could be doing anything—it just freezes me and I have to stop and hone in on it. It’s always been like that. It’s one of the few things that makes me really happy, when that happens, when you can feel a part flow into its home. You can visualize where it’s going to go and how it will be constructed, and you can envision its outcome. As soon as the current of it goes through, it’s like a giant release. It’s so uplifting. I try to leave an open space for decisive concepts or riff cycles, but if something continues to visit me, there’s usually a total shutdown moment until I go grab my bass and capture it.

There’s no guitar in Om. Why not?

It wasn’t intentional. We felt immediately upon playing in the room, that first day, that there was so much to explore, and it felt so right just between Chris and I that no more augmenting was needed. There’s a lot of interplay with the elements of rhythm drumming, the bass lines and the syncopation of the vocals. Purely sonically, the vocals actually play riffs. Obviously there’s always the bass line, but the vocals and the way Chris plays coalesce to serve almost as a riff on top of it. Even since I was a teenager, I’ve noticed that breathing and rhythm, they’re tethered together. The rhythm that you hear in drumming is comparable to a flywheel inside the central nervous system: the respiratory currents in motion, in a cycle. Another reason there’s no guitar in Om is we had already been in a so-called “heavy guitar riff” band. We wanted Om to go forward from where we were at the moment, not go back. And on a purely musical level, I dunno, I got kind of burnt on orthodox rock or metal songs, it’s almost like a cookie cutter. If the song calls for a solo, more the better, but… When we made our first recording, we looked over to the side of the mixing board where there were a bunch of empty guitar stands and just started laughing. [laughs] It’s nothing between us and guitarists! Good god, no. Highest ultimate respect to guitarists—that goes without saying.

Why are Om songs so long?

It’s not preconceived. When Chris and I start to get something going, it tends to call for repetition. I mean, there’s movement within that, and there’s shift, there’s change within that, but the overall expansion of it… It takes us where it leads us. We just do what they say to do: the songs, the pieces. Om is just who we are—where we’re at in the journey of our life. It’s a summary of the moment and the way the universe appears to our perception at this one second. It’s real, to us.

Lyrics are obviously important to you: the vocals are enunciated and the words are printed on the album sleeve. But the tenses aren’t always consistent, and sometimes the words aren’t standard English: “The swans array — the crane stands veiled grace — tunnement to the omen of the object form/And lighten pon day — as scintillate rays — augurate arrival of a seraphic form.” There seems to be a narrative, but…

The lyrics are just verse fragments—poem-prayers that spew forth from the mist. They’re definitely not constructed in the sense of grammatical soundness. It’s more cathartic in that sense.

The lyrics that you sang in Sleep were usually about marijuana, which was a big deal in the final part of the band.

In the beginning and the middle too. At that time, I was just completely dependent on the creative space I had gotten into [with pot]. During that phase, it was a friend. It was an assist. Its use now is more centered around confirming whether or not a bassline is correct, or if certain parts are compatible. It’s mostly used for analysis at this point. Then, it was used for the beginning, middle and end of everything. Today I don’t actually like to listen to music when I use it; I just listen to the sounds around me. If things start to percolate, of course I’ll go grab my bass, but… Everyone has their own relationship to it. I’m just speaking for myself. I definitely look at it as kind of a botanical shrine.

Is the audience for Om different than the audience was for Sleep?

In Sleep, you’d look out from the stage, there’d be like 200 denim vests and the room would be filled with pot smoke. In Om, there’s still the pot smoke but there’s people from all walks of life, from all different age groups. That’s a noticeable difference. Whoever can relate to the music is welcome.

Your approach in Om is essentially devotional in its concept and execution. I’m reminded of spiritually minded bands like Mahavishnu Orchestra, which I know you and the Sleep guys were into…

Yeah. I think I was 17. I was at a friend’s house and he was saying, ‘I can’t believe you haven’t heard this.’ Put it on, put it on. It was “Inner Mounting Flame,” and on the song, “Awakening,”’ the break with Billy Cobham on the kit… He throws down this one break after McLaughlin subsides these chords. It was so decisive that we just got up and left the room. There was no point in continuing conversation. It was done. That evening had been closed by that drumbeat. And to this day I think that in terms of drumming, “Inner Mounting Flame” with Cobham is Mount Olympus. There’s nothing more. It’s all. Saying Billy Cobham is a great drummer is like saying the sun’s bright, but… I don’t even know what to say about Mahavishnu. It was so humbling. It was an epiphany to hear the potential of these musicians and their conviction. Hearing something like that can make you feel like you’ve just been messing around in a sandbox your whole life.

Pingback: NAKED GIRLS SMOKING WEED | The District Weekly