A Deeper Shade of Doom

How do the drone-metal bands Earth and Sunno))) get something out of nothingness?

By Brian Evenson

Photography and layout by W. T. Nelson

Originally published in Arthur No. 20 (Dec 2005)

EARTH: BLACKING OUT

In 1993 the Olympia, Washington-based band Earth released their second album, Earth 2. No drums, no voices, two guitars, nothing else. It was ambient music done by a demon on downers—highly lugubrious, with slowed-down underwater metal riffs. Earth 2 traded in the glam, stagy evil of classic heavy metal for a brooding darkness, simultaneously a descent into hell and a sort Buddhist chant pushing you toward either Nirvana or nothingness (you choose). It was the kind of wandering super-vibrating music that makes your leg tingle where you’d broken it ten years before. Not only was it something you couldn’t dance to, it was something you couldn’t move to. It slowly shut you down. And with each of its three tracks over fifteen minutes long, by the time you’d finished the album you felt like you’d never start back up again.

Earth 2 is the ur-album of drone metal (it’s probably not a coincidence that their name is the same one originally used by Black Sabbath). It’s nothing at all like the grunge stuff—Nirvana and Mudhoney for instance—that their then-label Sub Pop was putting out then. But after Earth 2, the band—really just guitarist Dylan Carlson and whoever he wanted to partner with at the time—moved in different directions. Phase 3: Thrones and Dominions, a hard-to-find album from 1995 that you can pick up on disk for around $90 (or at itunes for $9), added one more guitarist and, for one track, a drummer. 1996’s Pentastar (In the Style of Demons) was still drone-y but just a hair away from being a rock album: cleaner sound, drums on all the tracks, deliberate shapes to the songs (most of which ran around five minutes), and even some vocals.

Earth was never a very visible band. They never played many live shows, and the few they did were in odd circumstances and spottily attended, remembered both fondly and with a trace of fear for how jarringly loud they were. Attempts to record these concerts were often less than satisfactory to the band. So when Earth disappeared altogether after Pentastar, amidst rumors of low sales, legal problems and out-of-control drug use, it was hard at first to notice, since they’d been hardly visible in the first place. Except for a bizarre appearance in Nick Broomfield’s contemptuous 1998 documentary Kurt & Courtney —Carlson was a close friend of Kurt Cobain’s—that unfortunately raised his profile in all the wrong ways, Carlson seemed down for the count.

Not much was heard from him until 2002 when Philadelphia’s No Quarter label re-released Sunn Amps and Smashed guitars, a collection of demos which featured a pre-Nevermind Cobain singing on one of the tracks. This seemed to kick Carlson into a higher gear. In early 2005, Troubleman Unlimited released Living in the Gleam of an Unsheathed Sword, a two-track live album, with the title track running over an hour. They also put out a remix album, Legacy of Dissolution, which instead of offering the usual metalhead suspects serves as a meeting ground for the likes of Earth acolytes Sunn 0))), Sonic Youth collaborator Jim O’Rourke, experimental musician Russell Haswell, electronica artists Autechre, and Scottish post-rockers Mogwai. Since Carlson was the one to assemble the list of remixers, the album both testifies to Earth’s cross-genre interest and to his own changing musical sensibility. Earth—now an instrumental duo with Carlson on guitar and Adrienne Davies on drums—even started touring.

* * *

Hex; or Printing in the Infernal Method, released last month by Los Angeles doom metal label Southern Lord, is the first Earth studio album in nine years. Hex has a relaxed, desert quality to it that you’d be hard pressed to find in Earth’s earlier work. Something definitely changed between Pentastar and Hex, though with Earth having dropped off the musical map in between it’s hard to trace the path that leads from one to the other. Intrigued, I contacted Carlson for an interview, which we conducted by email.

Hex’s subtitle comes from William Blake’s 18th century prophetic poem, “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” and refers to Blake’s method of illuminated print. The full quote reads, “First the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul is to be expunged: this I shall do by printing in the infernal method by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away and displaying the infinite which was hid.” In other words, printing in the infernal method is a way of both working against the Cartesian notion that the body and soul can be separated, and a way of revealing the infinite that (according to Blake) hides in all living things.

Carlson says his use of the quote “refers to a change in the philosophy behind [Earth’s] music. When I was younger, I was definitely held in sway to a sort of abstract dualist/Manichean world view. That the material world was wholly and irredeemably evil and corrupt, and that there was a world of the spirit completely separate and hidden within the material…. I guess I am now a monist instead of a dualist, I think the physical is a manifestation of the spiritual. That the two are interconnected.”

We’ve trained our senses in such a way that we don’t always see the things that are there, partly due to the way that European thought privileges vision over all the other senses.

“The spiritual is only hid within the physical because of our inability to perceive it properly,” says Carlson. One of the ways we perceive improperly is always relying on sight, to the exclusion of our other senses. Music is able to escape the mistakes of the eye and physical sight. We can hear the continuum of the physical and spiritual in the drone.”

This notion—the body is not distinct from the soul—became part of Earth’s music itself, both in terms of musical history and on the level of the sound itself.

“[T]he small colorations of different genres that are on the surface of the music could be likened to the body, and the drone that is within and behind it all considered the spirit,” he says. “On earlier Earth projects there were the more ‘metal’ figures or riffs and on this album there are more ‘country’ type figures or riffs. I have begun to see music as a continuum—especially the American forms such as blues, country, and jazz—and am situating myself within that continuum instead of apart from it.”

Both Hex and Earth 2 push through to something infinite. In Earth 2, that melting is achieved through repetition, drone, and feedback that somehow punches, after a kind of overload, through to something really sublime. Hex definitely doesn’t operate by overload. There’s a sense of space and openness and landscape, and a stillness not really present in Earth’s earlier work.

“There is a greater sense of stillness to this record that helps invoke the infinite,” says Carlson. “Also I am using ‘cleaner’ guitar tones than previously, which create a purer sense of the note. The notes are not hidden in oversaturated distortion. The spiritual is being manifested instead of hidden, as it were.”

Along with the spiritual dimension, there’s a decidedly Western feel to Hex, which pays tribute on its sleeve to Blood Meridian (author Cormac McCarthy’s grim high-literary rewriting of the old West) and Neil Young’s Dead Man soundtrack. The music itself is shot through with the ghost of the godfather of the Western soundtracks, Ennio Morricone. McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, with its incredible intensity, real sense of landscape and amazing passages of violence, seems especially apt. What was it, I asked Carlson, that he wanted to capture in that novel?

“The sense of the American continent being a place of extreme beauty, but also extreme violence and tragedy. Also, there is so much revisionist bullshit written these days portraying the conflicts of the emerging culture on this continent as the all-evil white man versus the all-good and benevolent natives. Blood Meridian paints a varied and realistic portrayal of the savagery that existed in all communities on the American continent at that time.”

* * *

On Hex, there’s no singing, but drums throughout, and lap and pedal steel as well. Reverb still interests Carlson; distortion and fuzz do not. He’s switched to a Stratocaster, and the drone is purer; it becomes part of a structure of the song itself, something to create a sense of openness and emptiness instead of something meant to blow your eardrums out. “My choice of guitar speaks to stripping down and making plain as well,” says Carlson. “I use a Fender Telecaster, the first guitar designed from the ground up as an electric guitar, rather than an acoustic with a pick-up added. The Telecaster produces a very pure tone, you can really hear the wood and metal in its sound. Also it has definite parameters in which it allows you to work. When people speak of ‘Tele-players’ it’s almost the same as saying someone is a Buddhist or Catholic—it is almost a creed. I think that pureness of tone and purpose helps strip away anything unnecessary and allows the music to will out.”

Add to that the clear influence of country/western virtuoso guitarists and you’re into territory that would make any but the most confident metalhead a wee bit nervous. Southern Lord, best known as a doom metal label, would seems likely to be nervous as well.

“Southern Lord has been nothing but supportive,” says Carlson. “They gave me the time and budget necessary to fully realize this album. Recently I was setting up at a show we did with Sunn0))) in L.A. I was using a 2×12 Ampeg combo, and I made a comment about feeling strange to not be setting up a mountain of cabinets. [Sunn 0))) member and Southern Lord chief] Greg Anderson said that I had been there and done that and had nothing to prove. It was incredibly liberating to be treated with that kind of respect.”

In any case, even if Hex is a real departure, it’s not completely unexpected. Earth has stayed in motion over the years, changing styles from album to album. But is there something that ultimately connects all these albums together, a common factor that allows Earth to go in different directions but still be Earth?

“The albums are each different surfaces but what is inside them is the same. I think no matter what I do that there will always be certain constants. The tempos will always remain slower than most. The drone will always be present.”

* * *

If you can bundle all the cues the album and Carlson are giving—Blake, McCarthy, the old West, the notion of being part of the continuum instead of outside it, the physical as a manifestation of the spiritual—you being to hear differently: you start to hear what’s there rather than what you expect to hear. And what you hear is that Carlson’s figured out the hidden connections between drone and the guitar work of the American folk and country tradition. Hex creates a fragile bridge between the two.

Does this mean Earth has mellowed out? And if I like it, does it mean I’m growing old and soft? Have I become the kind of person who likes to sit on the porch listening to country music? Well, not quite yet. But has Carlson? Or does he still feel an affinity for the kind of music, like Sunn 0))), that seems to have spawned from Earth 2?

Says Dylan, ” I respect what Sunn0))) is doing and other bands that are working in similar areas—I view them all as unique and important to music….” But at the same time, “Country is the genre I have the most interest in at this moment, mainly from a purely technical guitar-playing stand point. It uses a lot of drones (as pedal tones) in banjo rolls and oblique bends (bends against static notes). It is also one of the genres in which the Telecaster guitar has dominated and become most associated with. I have never considered Earth to be a genre band, although many seem to consider us metal or ambient or noise/experimental, so if people want to call us country too [because of the use of lap steel or banjo on Hex], that’s fine. Maybe having one more genre added to our output will hopefully help out in sort of a niche-marketing kind of way. I used to tell people when they asked me where I saw myself in 20-25 years that I would be playing electric guitar or pedal steel in a little country group in some bar somewhere like Oklahoma.”

Hex, to be fair, is still a long way from being the kind of music you can see in a bar in Oklahoma, even though Dylan has appropriated a lot of instruments commonly associated with country. It still has still the moodiness of Earth 2, but there’s a landscape being built up as well. It’s much close to the latest moody Dead Hollywood Stars EP than to doom, but the doom connection is still there. The darkness is more sober, calmer, but it’s still there, and it builds slowly and compellingly. Sometimes, like in “An Inquest Concerning Teeth,” it takes a momentary upbeat turn before slipping down again. The darkness is given a setting that lets it breathe rather than making it claustrophobic. Rather than the more aggressive and flailing darkness of Earth 2, Hex has an occult feel to it, like a spell, with full knowledge and with open eyes. The results are at once haunting and incredibly listenable, the sounds rich, rather than oversaturated.

And though I’m a huge fan of Earth 2, an album which I only discovered a few years ago due to Sunn 0))), I’m convinced Hex is the best and savviest of several very strong Earth albums. Hex is one of those few albums that make me think about music I thought I knew in a radically different way. It not only makes it possible rethink everything that Earth’s done before; it allows a glimpse at the hidden connections between diverse musical styles that have always been there but have never been so masterfully revealed. It makes me hear music differently. Carlson catches the hints of drone that have always been in country-western and makes me listen to them, starting to reveal the mysticism buried in the history of the West. Earth has moved from blowing out eardrums to rearranging the musical world I thought I know.

SUNN 0))): HEARING DOUBLE

At first it feels great to be imitated; it makes you feel relevant, necessary, important. But if it goes on for too long it can start to feel a little creepy, like your imitator is trying to become you, to take whatever claim to originality you possess. Ultimately, having someone around who acts like you makes you wonder who you are. It erodes any firm foundation of identity. And if he becomes you, then what exactly is left for you to be? That’s the problem, French philosopher René Girard says, with doubles. They’re at once the same as the thing that they’re doubling and weirdly out of focus, at once something and nothing.

Most of the time it doesn’t get that far. Most imitators are polite and controlled, respectful of the person or thing they’re modeling themselves after. But sometimes there’s a ritual aspect of imitation that seems to be trying to short-circuit the way we perceive the world. Take Elvis imitators: the best ones are not interested in being so much the next big star as in—by repeating his vocal patterns and gestures—bringing Elvis back to life. Through a process of ritual and repetition they open their bodies up to the King’s energy: the whole process is about getting to that brief moment where both they and the audience forgets that they’re not Elvis, where the repetition of a certain flick of the head and a signature gyration of the hips take them out of their bodies, leaving a kind of Elvis aura behind. When this happens—and it only rarely does—it’s uncanny as hell. It feels like time and space are being cracked wide open.

Cover bands and most tribute bands end up fitting into the polite and controlled category. The ritual is there—the repetition of certain vocal patterns and repeated notes—but you never get to that point where the musicians are transformed into the music. The ritual of repetition isn’t leading anywhere, identity is neither built nor eroded, and the experience at best is a pseudo-faithful version watered down with nostalgia.

Real artists, on the other hand, often transform someone else’s song to such a degree as to appropriate it and shift it into an entirely new space: there’s enough difference between Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix’s versions of “All Along the Watchtower” that you can enjoy both without feeling like you’re betraying one or the other. The same is true of Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” and M. Ward’s “Let’s Dance.” But how often do you find a band that’s able to remain slavishly faithful to their mentor and still get anything done? Such a band would, like a double, be in that strange space between being and non-being. You’d feel what they’re imitating almost constantly. Their act of ritual and repetition would be at once destructive and transformative: something that builds and builds so that by the time they reach that thirtieth signature gyration or signature chord, something suddenly happens that makes the air buzz.

If anybody comes close to doing this, it’s Sunn 0))).

* * *

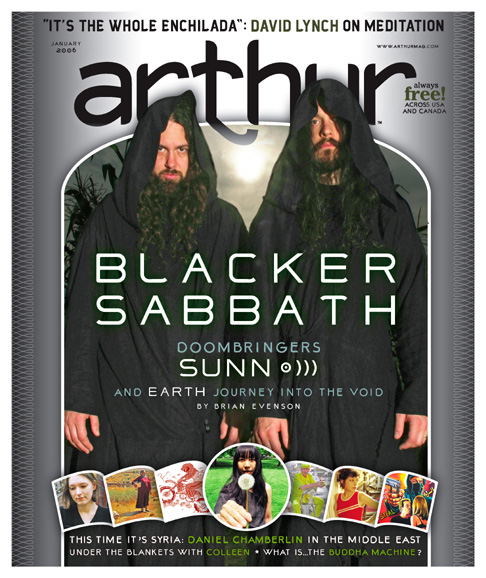

Sunn 0))) started in 1998 as a side project for former Burning Witch partners Stephen O’Malley and Greg Anderson in honor of the band Earth. Both Anderson and O’Malley had witnessed Earth live in the ‘90s, and repeated playing of Earth’s two albums turned them into diehard Earth fanatics. Sunn 0)))—pronounced Sunn, the “0)))” is silent—named themselves after Sunn amps, Earth’s preferred amps and then set about paying tribute to a band they felt had changed musical history.

Sunn 0)))’s first two albums sound like, well, Earth. O’Malley and Anderson learned their lessons well from Earth 2, taking full advantage of the aesthetic space Dylan Carlson created. Sunn 0))) acted like a fairly well-behaved tribute band, remaining faithful to a particular moment in Earth’s career. They were very good at capturing both the mood, the feel and the sound of Earth. It was enjoyable stuff to listen to, but you had less the feeling that musical history was being made than that musical history was being repeated, that the albums weren’t quite reaching the point where the ritual was releasing the more intense energy of transformation and negation.

But at something changed around the time of their third album, 2001’s 3: Flight of the Behemoth. The music initially wasn’t that different, but Sunn 0))) no longer seemed to be looking quite so adoringly at Earth’s past. Instead they were looking farther along a track that Earth discarded in favor of their very different evolution today [again, see left]. It was like they were imitating the Earth songs that had never been written, that they’d gotten so good at doing imitating Earth that they now were imitating the way Earth might have developed in an alternate reality.

This shift was first audible in the tracks Japanese Noise-drone veteran Merzbow mixed on 3: Flight of the Behemoth. “))) Bow 1” and “))) Bow 2” play like metal run through a noise ringer, moving a purer and crueler sonic attack straight out of the Noise tradition and then back out to metal again, with occasional pounding, dissonant piano. In the two albums that would follow, 2002’s White 1 and 2003’s White 2, there’s still an incredible faithfulness to early Earth’s doom/drone, but there’s also different kind of attention, a sense that Sunn 0))) were starting to hear an imaginary future. The difference, perhaps, was due to Sunno))) becoming a collaborative exercise involving outside musicians—O’Malley and Anderson had figured out a way to bring other people in to the mix, not so much as add-ons but as catalysts to mutate the band’s sound.

What’s amazing about Sunn 0))) is that the changes that have occurred feel almost like micro-adjustments. For someone who isn’t that familiar with Sunn 0))), the similarities between the albums is likely to far outweigh the differences; it’s only on repeated listening that one hears the progression slowly welling up. So, the ritual of imitating Earth demands also from the fan an almost ritualistic listening with greater and greater care, a real desire to find the strange and almost microscopic gaps where deviations both reveal a new direction for Sunn 0))) and reinforce their connection to Earth everywhere else. That’s the twist that makes Sunn 0)))’s later work like a double: it’s at once like Earth and slightly out of focus.

Sunn 0)))’s White 1 (2003) goes on record as the only album that’s ever inspired me to go out and buy new woofers (it’s also responsible for blowing out a lot of headphones). Because you’re listening for minute changes within a soundscape, the louder it’s played, the better it sounds. If you can locate the right spot a few decibels before your ears bleed and your speakers self-destruct, you begin to experience the uncanny.

I have a fond spot for White 1 since it’s the first Sunn 0))) album I heard. A few years ago a reader my fiction writing got in touch with me; one of the first things he asked was whether I knew about Sunn 0))). I’d never heard of them but went out and bought White 1. I was prepared for a metal band, but what surprised me was that I immediately could see connections between what Sunn 0))) were doing and what artists in other genres—noise, experimental, drone, ambient, and krautrock—were up to. It was the first metal band that I could listen to without feeling nostalgic, and also the first such band that I felt had a sense of negativity and nothingness and ritual that my own fiction was very sympathetic to. I felt like Sunn 0))) was emptying themselves out to make way for Earth, and I felt that the repetitions gave me permission to do the same as a listener. White1 gave you permission to stop being yourself for a while.

On White 1, O’Malley and Anderson were doing the solid slow-motion metal riffs that they’d done or earlier albums, but they’d added a few guests: former Melvin Joe Preston and guitarist Rex Ritter embellishing O’Malley and Anderson’s roiling sonic sea; Julian Cope reciting a narrative; Runhild Gammelsaeter singing a traditional Norse poem. They moved away from metal and toward experimental music in the last of the three tracks on the album. Instead of taking the drone away, they augmented it, throwing other things into the mix. “At one point,” says O’Malley, “we had to decide where to take it, so we started inviting people to perform on a song, perform live, etc. It’s very comfortable for us to try out different things and move in directions we like. The character of the people doing it is really the tone of what happens.”

I’ve never seen Sunn 0))) live, but everyone I’ve talked to who has suggests that it’s uniquely powerful in the same way the recorded music is, using a combination of effects to try to get to that moment in which reality is transformed. The performers wear hooded robes, and in some cases have their faces hidden. There are candles and rolling fog, and a decidedly ceremonial feel that combines with the dirge-like drone to loosen your joints and make your body vibrate.

On the one hand, it sounds like watching the Stonehenge sequence in Spinal Tap; there’s something comic and over the top about it, something silly. Sunn 0))) also never perform sober which, admittedly, is part of a long rock tradition, but in this instance seems to have a more serious, consciously ritualistic component: it is an attempt to get outside of oneself. O’Malley and Anderson are both smart enough to see the potential goofiness of their performance and I think that taking the risk of being considered goofy is part of the performance for them, a way of becoming vulnerable. If you are willing to go along with it, the ritualistic quality of the performance and the music allow you to become part of something much more amorphous.

For O’Malley, it’s less like a religion than learning how to be part of a rhizomatic sound machine: “We are tagged with the words camp, ritualistic, ceremonial, cheesy, theatrical, etc. These all could be valid as a point of view of the live performance. In the best-case scenario the audience is part of the experience, part of the vibration and the altering of space. Aspects of trappings like smoke and robes/costumes may seem over the top, but to me it’s a very direct set of tools to allow the actual method of evoking this vibrational energy to step outside the everyday and individualized aspect. All people in Sunn 0))) at that moment become subservient to the sound itself, not to the humanity of the people creating or accessing that sound. I strive to have an experience in a different perspective of space and time with every Sunn 0))) event.”

Selfhood dissolves. Your body and mind is transmuted into an annex of the sound. The audience, watching O’Malley and Anderson move into that vulnerable space, watching them give themselves up, is willing to become much more vulnerable themselves.

* * *

Both live and on their releases, Sunn 0))) is playing up this uncanniness more. While the recently released Black One has a healthy dose of the drone and feedback of 3, Flight of the Behemoth and White 1, it incorporates additional elements and takes new risks.

The short opening track is especially surprising in this regard; it plays like a mood piece. Says O’Malley, “The idea with the first track was to make a framework for the album, like those black metal records in the early 90s with intros and outros that use completely different instrumentation from the rest of the album.” The first piece on Black One was composed and performed by experimental musician Oren Ambarchi and is what O’Malley calls “A blatant attempt to drive into a cinematic space: ‘70s jungle cinema, voodoo, dark tribal.”

Black One has a very filmic feel to it, more of a sense of cohesiveness than previous Sunn 0))) albums, as if each song is a different scene within an overall theme or storyline. O’Malley managed to get the album’s genre listed as “Soundtrack” in on-line music stores, something which on one level is tongue in cheek but on another level gives listeners a clue about how to approach the album.

There’s still plenty of drone and doom on Black One, though the sound is slightly cleaner, and several of the tracks, such as “Bathory Erzsebet,” cross borders between metal and experimental music, shuttling back and forth between the two territories. Perhaps this isn’t surprising, since one of O’Malley’s favorite labels currently is Mego, the Austrian home of experimental musicians Kevin Drumm and Hecker. An experimental music festival that Oren Ambarchi runs in Australia led to the opening of a lot of musical doorways for the band. “It’s funny who you end up meeting on tour and festivals that you are connected with,” says O’Malley, right before he tells me about getting in touch with the Finnish electronic band Pan Sonic, who are not exactly doom metal, but do things with static and fuzz that Sunn 0))) feels connected to. It’s this willingness to look for allies in unexpected places that’s allowed Sunn 0))) to move from being a tribute band into being an uncanny double.

Black One has more of a vocal element than any previous Sunn 0))) album, but the vocals are screamed, distorted and buried in sound. They’re very difficult to actually hear, something that ties the band to black metal and doom metal music, but goes beyond, as if the voice is being used to embroider the drone and guitarwork. At the same time all the vocalists are actually performing lyrics: there’s a narrative quality, a story being told, a song being sung. A syntax is operating, but it remains mysterious and partly hidden, something that can’t be extracted completely from the music. In that sense, like some of the most interesting fiction writers working today, Sunn 0))) is dealing with abstraction, with the shimmer that comes in that ambiguous space between something that has all the structures of meaning but remains just out of the perceiver’s touch.

O’Malley says, “Live, we’ve done a lot of vocals with Attila Csihar, a Hungarian guy with a love of Indian music and opera. He has a physiological appreciation for being a vocalist, the way he uses his body to project his voice.” Vocals are an obvious way Sunn 0))) can change their sound, but they’ve done so by choosing vocalists who express themselves in a way that’s very instrumental. This attitude plays very well with the cinematic quality the album is after.

Sunn 0))) has a penchant for putting numbers into their album names is perhaps in part an homage to Earth 2. Black One recalls White 1, Sunn 0)))’s breakthrough album. Should it be seen as a kind of darker side? For O’Malley, it’s more a “phonetic connection, slightly a joke. The White Albums are very shadowy. The word ‘black’ in this album is more the void, no light, absence, negative space.” While most doom is searching merely for darkness, Sunn 0)))’s original relation to Earth has allowed them to understand nothingness in a way that very few bands do.

The fact that some of Sunn 0)))’s more recent stuff is stretching it for doom metalhead guys has enabled Anderson’s Southern Lord label, which releases Sunn0)))’s work, to expand their range and include, for instance, the newest incarnation of Earth. And Sunn 0))) has served as a kind of reverse doorway, bringing non-metalheads who are interested in noise, ambient and other kinds of drone to doom metal.

Says O’Malley, “Doom stuff gets to a regressive state of mind, stepping back into a more subconscious, primitive state of mind. But there’s lot of different ways you can enter that state of mind. Drone is probably one of the more natural forms of music, in terms of what exists in the world.” It’s Sunn 0)))’s ability to walk the line between the void and the natural world—not to mention the lines between originality and imitation—that make them the real thing.

Or maybe it would be better to say the real nothing.

Pingback: links « supervillain

Pingback: HTMLGIANT